Thoughts by Mr Creosote (06 00 2024) – Apple II

When things briefly looked like the medium of computer games would merge with the world of printed books, Telarium was one of the labels established exclusively to develop and market text adventures made in cooperation with established fiction writers. When their management approached Michael Crichton, even at the time one of the best-selling authors, they must have been surprised. Crichton had already started developing a game, hired a programmer and all. The two parties finally came to a publishing agreement, and Telarium had some final input into the game, but this history made the original Apple II version of Amazon unique in their portfolio insofar that it is not based on their in-house game engine. Only the later ports are.

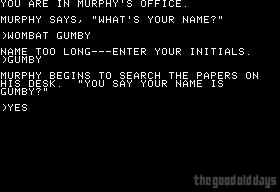

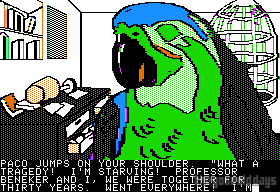

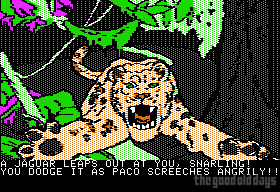

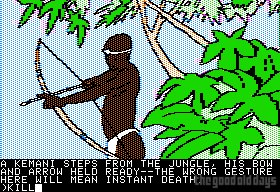

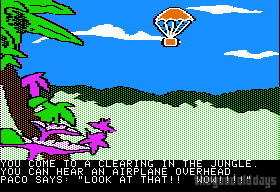

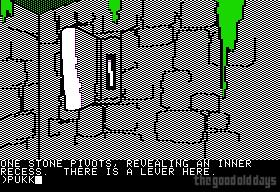

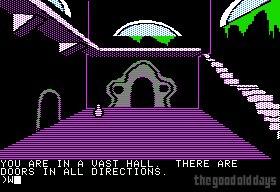

Not that it makes a huge technical difference. Crichton’s game is a mostly illustrated text adventure utilizing a fairly rudimentary parser. Based on his latest novel at the time he started development, Congo, the plot is vastly simplified and lightly adapted, because the adaptation rights to this book had already been sold. Instead of Africa, the protagonist travels to the South American rain forest. Meeting murderous apes, primitive natives and guerillas. It’s a world where nobody, including the protagonist, raises an eyebrow when a parrot not only imitates human speech, but is able to carry a meaningful conversation. And becomes an indispensable sidekick who, even when not helping actively, provides entertainment through his sarcastic comments.

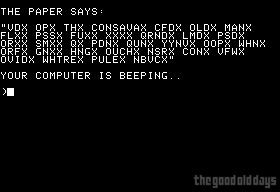

Congo’s basic plot structure lends itself well to a computer adaptation. Literally an adventure, the setting of wading through unknown jungle, avoiding dangers, was already well established in text adventure circles. Adding Crichton’s usual fascination with semi-futuristic technical gadgetry, Amazon provides a thrilling mix.

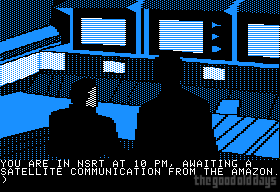

What certainly also helps is that basic storytelling techniques have been applied. The game opens with a short transmission from the Amazon area. Dead bodies. Suddenly, a masked figure jumps the camera and destroys it. The protagonist is summoned to the boss’s office. You’ll be leading the next expedition into that area. Good luck!

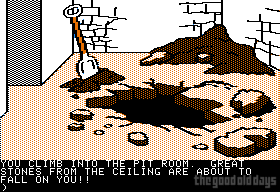

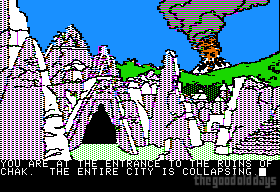

Before arriving in South America, there is equipment to be procured and a team to be assembled. This provides a smooth way into the game and the expected interaction model with few dangers for a start. And it also slams in the next storytelling beat when the key member of the expedition turns up murdered. Then, on to the fictional world of wild animals (including a hippo, probably escaped from the zoo), murderous cannibals, crumbling rope bridges and a volcano threateningly looming on the horizon at all times.

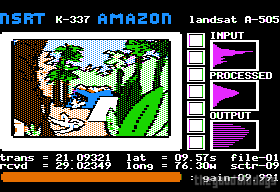

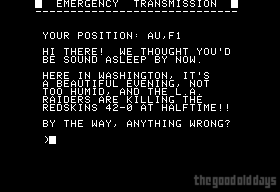

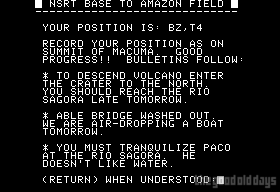

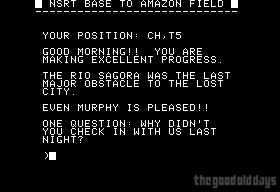

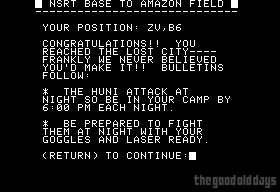

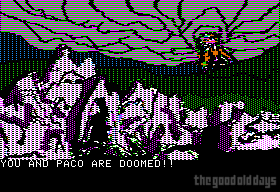

Real puzzles are few. The difference the three difficulty levels make are in the amount of instant death traps. Navigating one’s way through the jungle without running into those, which is largely a game of chance. That aside, and depending on said difficulty potentially including, the game provides pretty clear directions what to do next. Through the talking parrot. Through the regular satellite calls with home base. Explicit guidance makes the steps clear, but also provides a constant sense of urgency by pointing out the dangers, highlighting the deadlines enforced by nature (the volcano…).

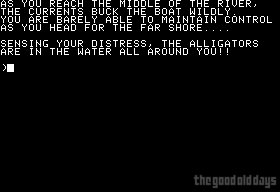

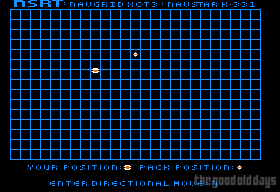

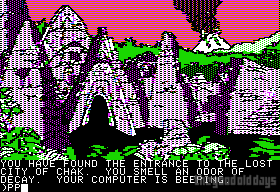

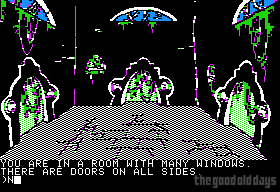

The game thus becomes a breathless forward movement. At a time when nobody owned a mobile phone personally and certainly did not carry a GPS receiver in their pocket, the whole idea of traversing the jungle, the large printed map from the box next to the desk and supported by location coordinates on the screen, was breathtaking. Using the night vision goggles to escape the rebel camp still works as an immensely tense scene. Finding a lost city… it’s one of the classic motifs in the genre.

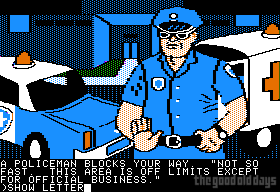

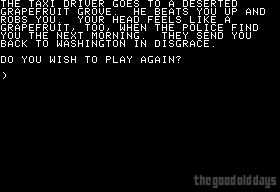

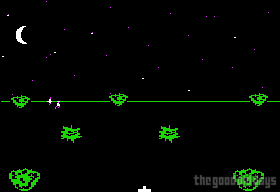

Were the two simplistic action scenes, very likely added by Telarium in the spirit of the other games they had in development, needed? Surely not. Though they are impossible to lose and easy enough to win. Was it a good idea to have the first flight sometimes randomly end the game in failure? Surely neither. That, of course, is where Michael Crichton’s inexperience as a game designer (and the lack of fully formed design conventions at the time) shows.

In the big picture, it doesn’t matter. Amazon remains a fine game. Reportedly selling above 100,000 copies, it did not quite reach the heights of Infocom’s The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy, but could still count as a significant success. Though of course, if you’re Michael Crichton, this number will not mark a noticeable spike in your bank account. He didn’t return to designing a computer game until more than ten years later. But at least, Amazon remained proudly on his CV until he died unexpectedly.